Editor's Choice

What the Court Records reveal about Stationers’ Hall

Sarah Hodgson

The Court Records included in Literary Print Culture are essential to our understanding of the history and workings of the Stationers’ Company. The Court Books, ranging from 1602 to 1983, contain the official minutes of the Court of Assistants: the Company’s governing body consisting of a Master, two Wardens and a varying number of assistants. For each meeting, the decisions of the Court are recorded as orders. The collection contains the rough Court minute books and the Court books; the former being draft minutes taken while Court was in progress, and the latter being the formal and final version. All minutes were signed by the master and typically the following information was included: place, date, time of court meeting and a list of those present.The orders cover various topics such as: movements of shares within the English Stock, charitable donations, binding of apprentices, cloathing and being made free of the company.

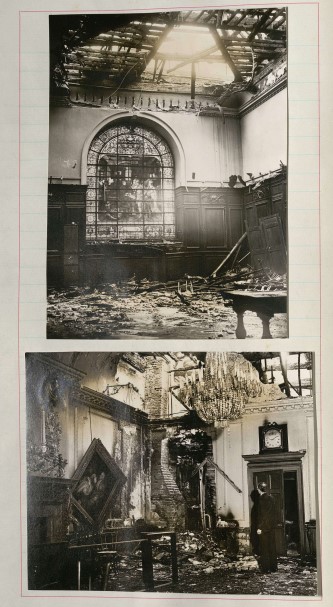

Court minute book k, dating from 1 Feb 1938-3 Jul 1945, stands out for the simple reason that it contains photographs, which is unusual for the court minute book collection. The photographs, pictured here, show the bomb damage to Stationers’ Hall, located on Ave Maria Lane in the City of London, in 1940 during the Second World War. The minutes reveal that an incendiary bomb was dropped ‘from an enemy aeroplane’ between 1 and 2am on Tuesday 15th October 1940 onto the roof over the lobby to the court room. The court minute book records that ‘the housekeeper and his wife were sleeping in the basement near the Beadle’s office, and were not aware of the falling of the bomb till the Hall was well alight and fireman were engaged in putting out the flames.’ As a result of the fire, the attic over the lobby to the Court room and the roof of the Hall were almost completely destroyed along with other parts of the building. Objects including portraits, shields of the arms of the masters and gowns were also lost along with papers and books. Fortunately, the company records were mostly safe. The minutes go on to reveal how plans were put in place to remove ‘all items of historical or intrinsic value whether fixed or moveable.’ A recommendation for replacing the roof is also discussed. The entry is a fascinating insight into how the Second World War directly affected the Company and its employees and how the archive could have been lost.

The Court Records can be used to reveal so much about the rich history of the Stationers’ Company. References to the bindings of apprentices, members present at meetings and records of deaths, amongst other topics, can be researched alongside the Membership Records, while references to the English Stock provide links to the vast collection of Trade Records. The Court Records work to shed light on the unique history behind the Stationers’ Company and offer researchers extensive opportunities to create links across the different record types.

Thomas Carnan vs the Company of Stationers: ending the almanac monopoly

Sara Hussain

In 1744, a young man welcomed a historic legal victory by apparently driving ‘repeatedly, in triumph, round St. Paul’s Church yard and through Paternoster row, in his lofty phaeton and pair’.[1] Thomas Carnan was an enterprising individual who had moved from Reading to London and who had his eye on the profitable market for almanacs and other such useful items with equally nebulous definitions. In his way, of course, was the Stationers’ Company. In 1603, the English Stock was established by the Company to capitalise on the monopoly granted them by King James I, which gave them the sole privilege to print certain religious works such as primers, psalms, psalters, and also almanacs and prognostications. More than this, the privilege was to last without end, meaning the Company and its Stock printing and publishing arm was in a highly lucrative position.

The case of Thomas Carnan vs the Stationers’ Company built on the victory of Donaldson vs Beckett of 1774, where the perpetuity of copyright was challenged. Carnan’s own success came on 29 May 1775 when the judges ruled that the Company and the English Stock’s grant only covered approved almanacs and that not only could such copyright not last in perpetuity, but that it could not be granted exclusively.

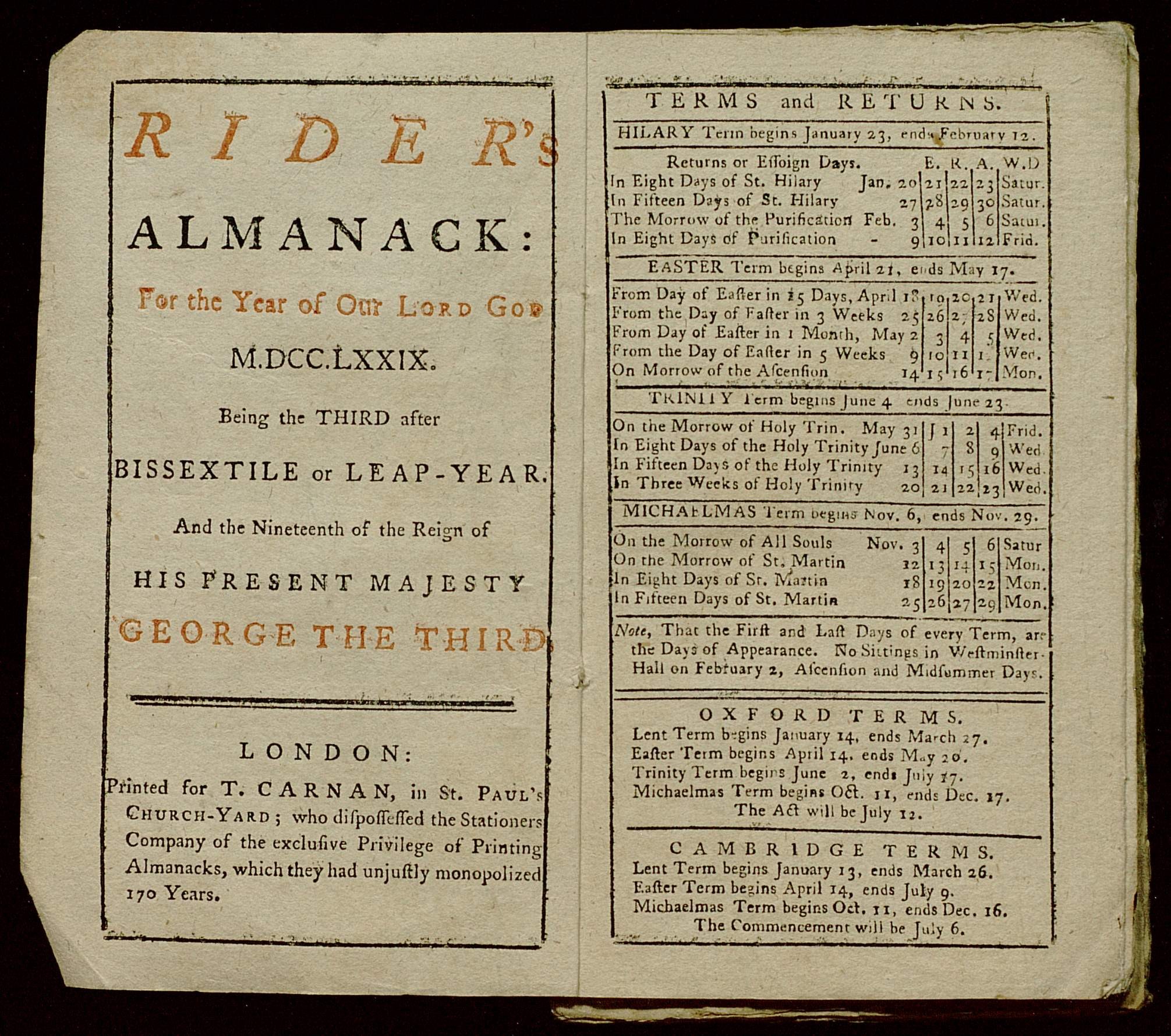

The proceedings of this case are detailed in the Trade Records, in the Thomas Carnan dispute subseries. Here, the researcher can start with a look at the offending articles – examples of the kind of almanacs printed by Carnan, which Cyprian Blagden believes showed off ‘Carnan’s better standard of printing and more up-to-date Almanack [sic] compilation’.[2] One of the items from 1779 proudly states ‘Printed for T. Carnan, in St. Paul’s Church-Yard; who dispossessed the Stationers Company of the exclusive Privilege of Printing Almanacks, which they had unjustly monopolized 170 years’.

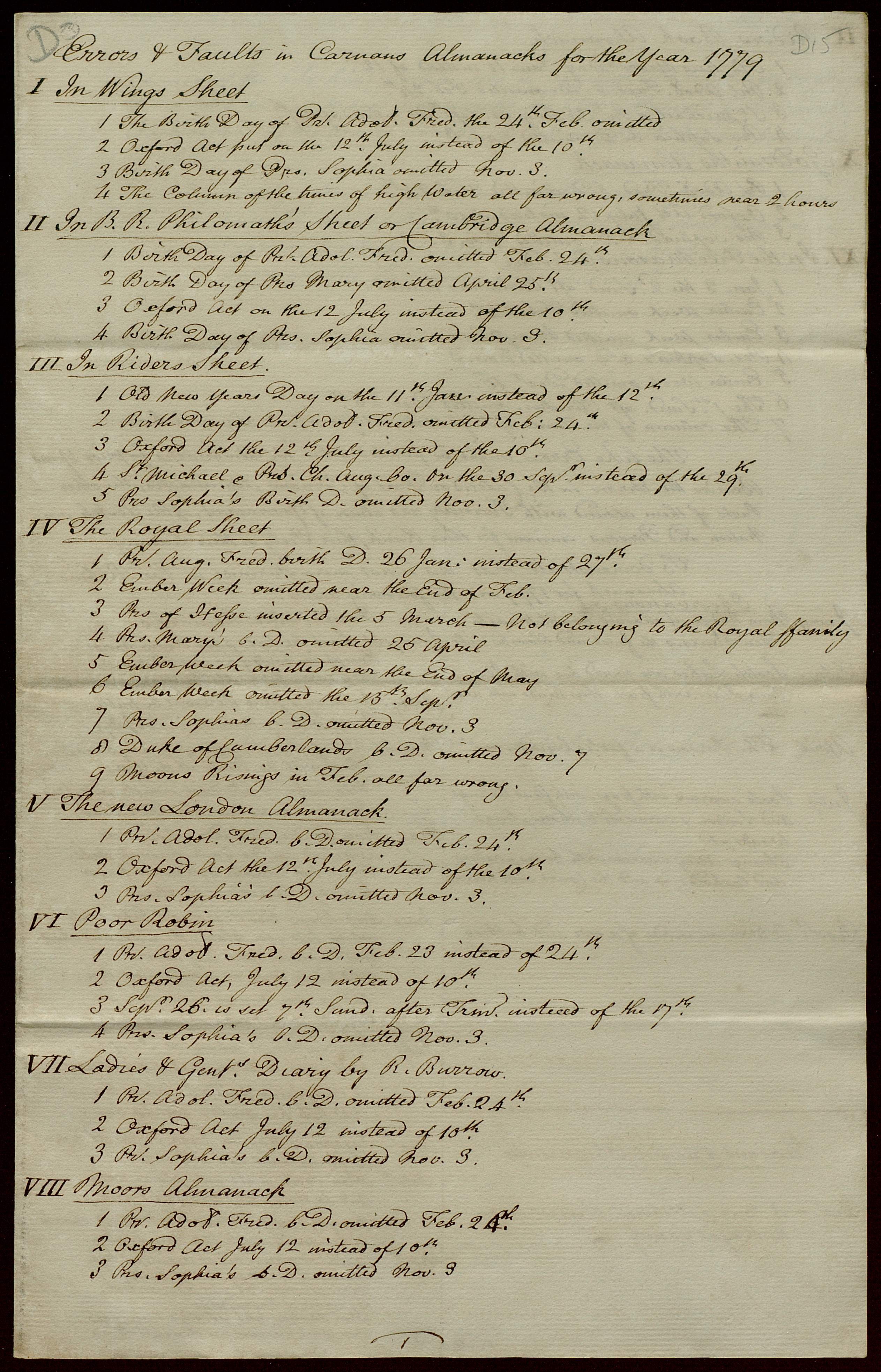

Not everyone was convinced of Carnan’s superb printing, however; the Company took the time to list faults they had found in his work, years after the ruling which shook their monopoly.

Such endeavours might have been undertaken to build up a case against the ruling. The fastidiousness of the list has to be admired: the author writes that ‘the like errors might be pointed out in the almanacks for prior years besides the errors in the calendar part of Carnan’s almanacks, the other parts of them abound with scurrility and abuse of government, of the Scotch nation, and persons eminent for their rank, their piety or their learning’. One of the examples of such slander he claims to have found includes the words ‘Scotch lakes are cover’d o’er with ice, their hills with frost, their heads with lice’.

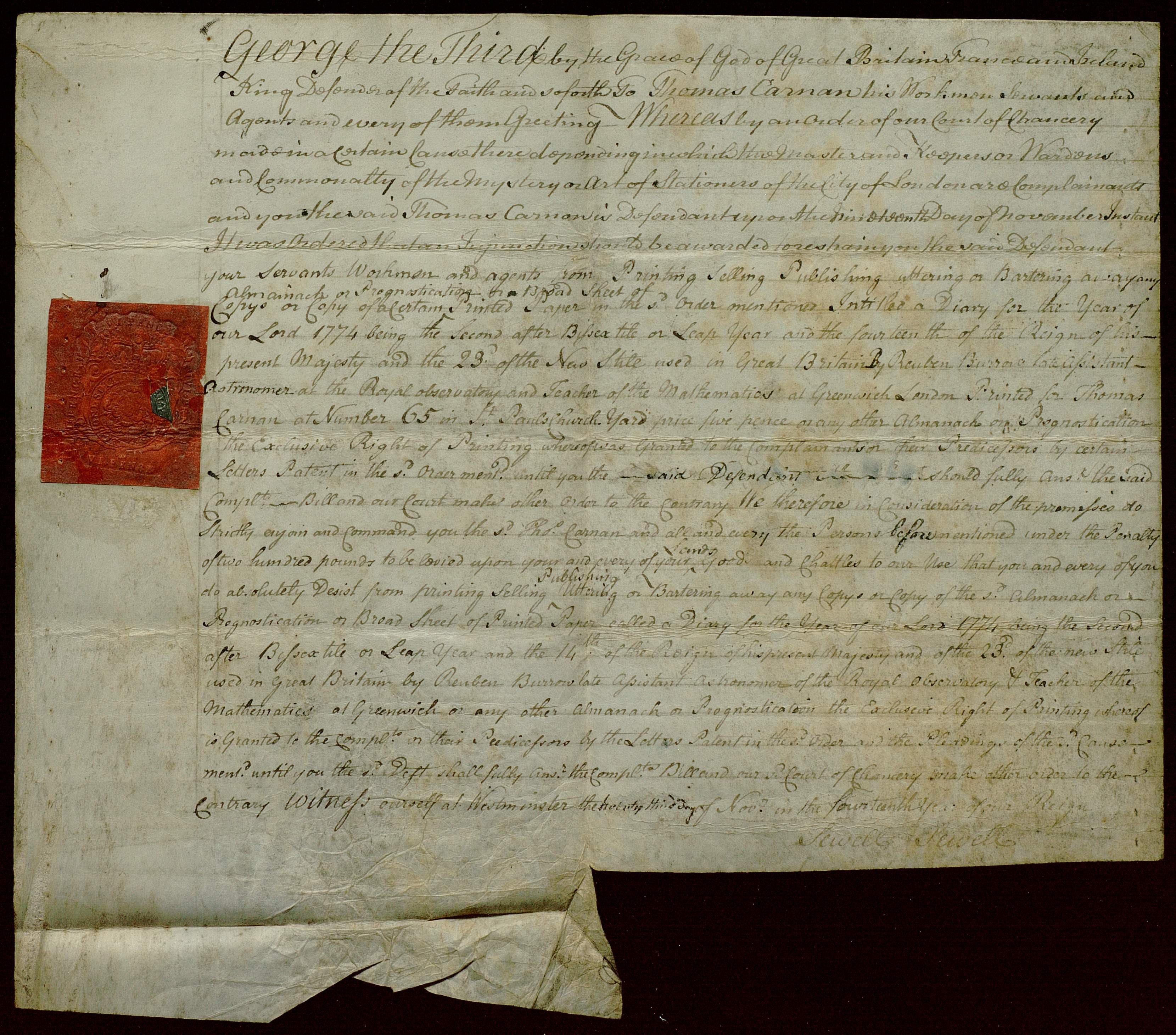

Other efforts to have Carnan cease and desist included an injunction put upon him in November 1773, in which the Company reiterates their ‘exclusive right of printing’, with failure resulting in the levying of a £200 fine.

Carnan’s perseverance and victory in 1775 marks a watershed for the nature and role of the Company within the copyright sphere, and provides a unique and useful point of commencement for further research into its history. It also touches upon other players within the world of printing, publishing and copyright – such as the universities of Oxford and Cambridge – and of ideas such as the control of the printed word and its relation to government and religion. Carnan himself, however, was free to concern himself with the profitable world of almanac printing without worry, as shown by his jaunts in his phaeton in the heart of the City.

[1] W. West, Fifty years' recollections of an old bookseller (Cork: printed for the author, 1835), 21, via http://www.copyrighthistory.org/cam/tools/request/showRecord?id=commentary_uk_1775, accessed 19/04/2017, 12:07.

[2] Blagden, Cyrpian, ‘Thomas Carnan and the Almanack Monopoly’, Studies in Bibliography, Vol. 14 (1961), p.34.

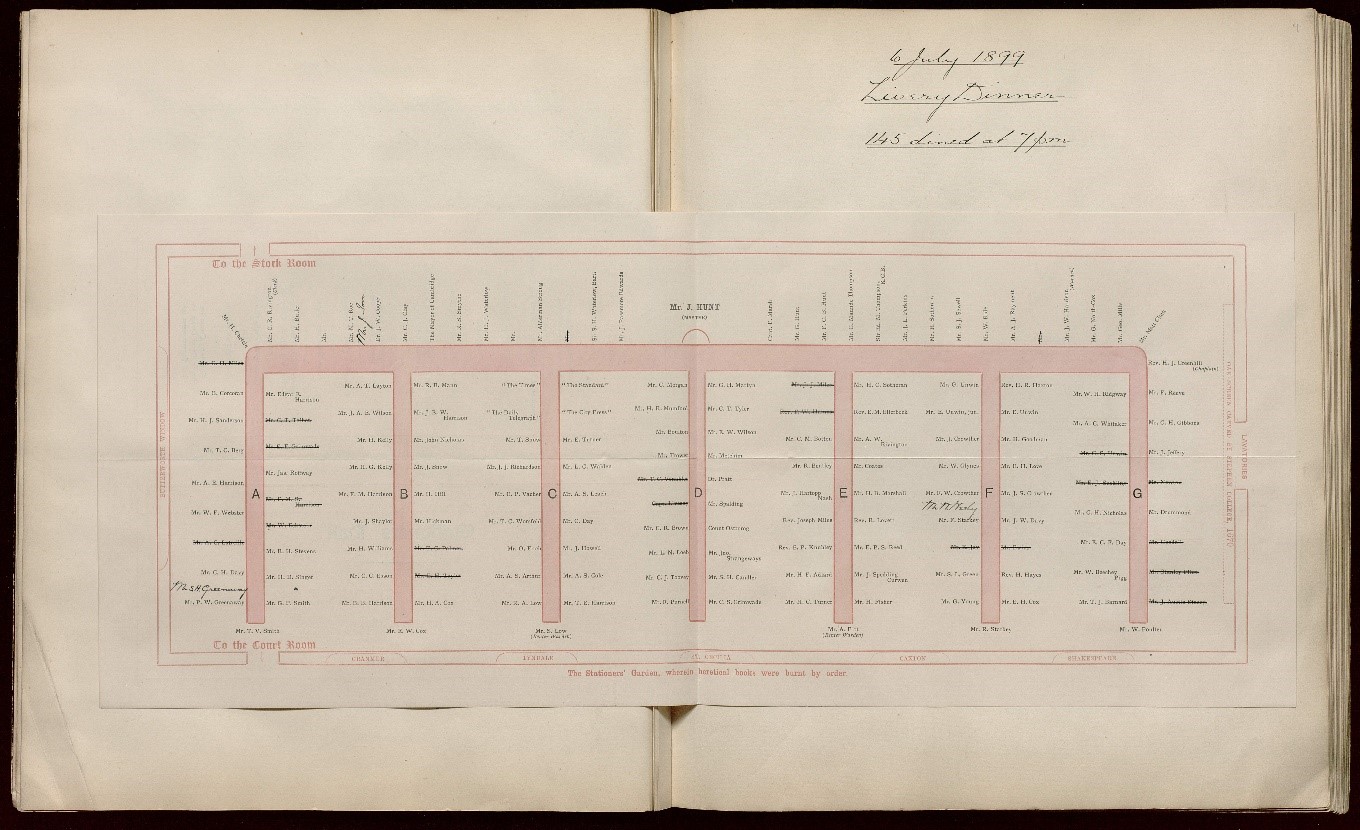

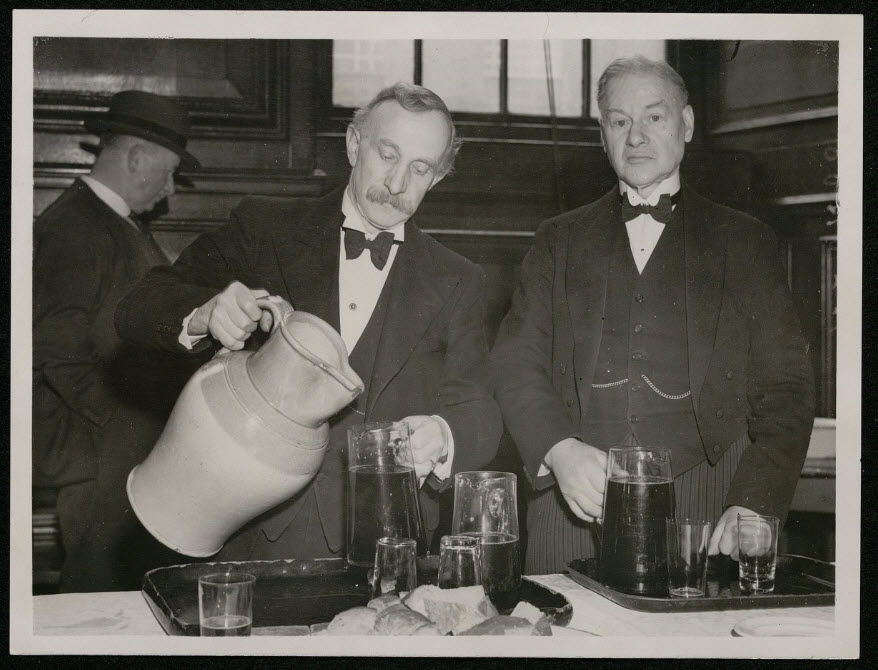

Dinners of the Stationers' Company

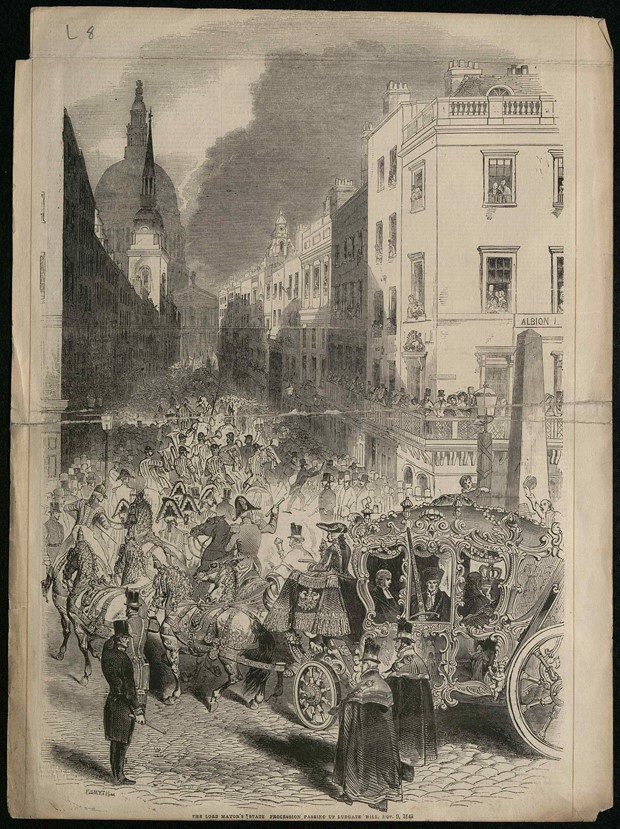

The Royal Charter of 1557 bestowed upon the Company certain rights and privileges beneficial to both its members and the Crown itself. It reinforced the customs the Company had adopted from their earlier inception as a guild of the City of London. One custom in particular, which features in this collection, is that of the dinners and social gatherings held by the Company’s members. Since the move to their first hall, Peter College in St. Paul’s Churchyard in 1554, the importance placed on dining has been significant. The Company held a variety of gatherings throughout the year; along with Livery Dinners there were the Election Feast, Ash Wednesday, Ladies’ Dinners, Lord Mayor’s Election Day, and the Lord Mayor's water procession down the Thames river.

The Quarter Day meetings held every three months throughout the year were quickly established as an essential part of the Company’s proceedings. While a great opportunity for gathering their colleagues into one place, the chance to socialize with their fellows wasn’t the main reason members were expected to attend. The meetings were an opportunity to discuss and resolve any grievances and to reaffirm the Company’s rules and regulations. Before the dining could take place, the ordinances were read out and the members were obliged to make payments to the Renter Warden for the ‘quarterly dues’. In 1884 the Court abolished quarterage and three years later the Renter Wardens were relieved of their obligations. The dinners continued but were hence forth referred to as simply Livery Dinners.

Hearing the ordinances served as a reminder of the Company’s laws and regulations, while also being a good chance for new members to learn the ropes. They would have covered a variety of regulations which were vital to the running of the Company. The ordinances of 1878, for example, stated that members must attend each gathering in the livery gowns, refrain from “brawling and bad language” and those who dared to disobey the ordinances would be faced with a fine. The ordinances were fundamental in educating Apprentices in the craft’s policy and the procedures they must all follow to eventually become Freemen.

The Election Feast (or Venison Feast) was always held on the Sunday after St Peter’s Day, 29th June, and was the day Apprentices were elected into the Company, thereby becoming Freemen. After seven years of servitude to their Master, an Apprentice was unbound and given the freedom to trade in the City of London. Upon election via majority rule, a Master would present the new liveryman with a livery gown. After the Master placed the gown over the freeman’s shoulders, “the said Master and Wardens, each in their order, shall give to such person … his and their hands, saying these words, (Videlicet) Brother, you are Admitted to the Cloathing of this Company; or words to that effect”.

The Company’s Ash Wednesday feast (also referred to as ‘Cakes and Ale’) has remained one of the most prominent gatherings in the Company’s calendar and has continued to this day. Under the terms of the will of John Norton (1557-1612) a modest repast of ale and buns made to a special recipe (now lost) was provided on Ash Wednesday, after which the Company processed in order of precedence, robed and preceded by the Beadle, to St Faith's Church in the crypt under St Paul's for the Ash Wednesday service.